Ask any seasoned feedlot operator what keeps them up at night, and the answer is almost always the same: Shipping Fever. Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD) remains the single costliest health challenge in cattle feeding, accounting for the vast majority of illness and death loss in feedlot cattle.

Here’s the hard truth: the game is won or lost in the first 14 days. How you receive, process, house, and feed newly arrived calves during that critical window determines not just their immediate health, but their performance for the entire feeding period.

Get it right, and you’re setting the stage for strong gains and minimal pull rates. Get it wrong, and you’ll spend the season chasing sick animals and shrinking margins.

This guide breaks down everything you need to know about managing calves in feedlots from the moment they leave the farm gate to the point they settle in and start gaining.

Preparing Your Operation Before Receiving Calves

Success on receiving day doesn’t start at the chute; it starts weeks before the truck arrives. Thoughtful feedlot calves preparation can significantly reduce the stress and health risk these animals face during the transition.

Source Healthy Calves

Before you buy, do your homework. Request vaccination and health records from the seller, and avoid purchasing calves with known disease exposure or unknown origin history. Source from a single, reputable ranch when possible, rather than multiple small groups. Commingling calves from different origins dramatically increases disease transmission risk, since each group carries its own microbial profile.

If preconditioning is an option, meaning calves were weaned 3–4 weeks before shipment and received a starter vaccination protocol, that’s worth pursuing. What matters most is documentation: know what vaccines were administered, when, and with what products. Also, record any previous implant or medicated feed history, as this directly affects your receiving protocol.

Reduce Transport Stress

The trailer ride is one of the most physiologically stressful events a young calf will ever experience. Temperature swings, noise, motion, and crowding spike cortisol levels and suppress immune function before the animals even set foot in your pen.

Use well-ventilated trailers with adequate bedding, and never overload. A 500-lb calf needs approximately 8 square feet of floor space. Keep time in holding pens to a minimum, and insist on reputable, experienced drivers. On long hauls, having two drivers can meaningfully reduce transit time and arrival morbidity.

Plan Initial Processing

Have everything ready before the truck arrives. That means vaccines, dewormers, and implants staged and within label temperature ranges, a clean working chute no wider than 24 inches (appropriate for calves up to 1,000 lbs), and a designated sick pen with separate feed and water that’s isolated from the main receiving pens. Planning initial calf processing prevents rushed decisions and missed protocols on arrival day.

Managing Newly Arrived Calves in the First 24 Hours

The first hours after arrival, calves reach the feedlot and set the tone for everything that follows. Stress reduction is the primary objective, not speed.

Calves Rest and Settle After Transport

Rushing stressed calves into processing costs you more than the time you think you’re saving.

Gentle Unloading

Move calves off the truck calmly and quietly. Avoid electric prods and loud voices. Let them walk at their own pace into a prepared receiving pen that already has fresh water available. Cattle are prey animals; sudden noise or aggressive handling spikes adrenaline and slows the recovery process.

Allow Rest

If calves arrived after a long haul or appear visibly stressed, give them 6–12 hours of rest before running them through the chute. A quiet recovery period lowers stress hormones and primes the animal to begin eating and drinking. Keep the pen small and shallow so animals are never far from feed and water.

Observation

Once calves are settled, observe them from a distance. Watch for signs of exhaustion, lameness, or respiratory distress like drooping head, coughing, nasal discharge, or labored breathing.

Also, take rectal temperatures on any animal that looks off. A fever above 103.5°F is a red flag and typically the first measurable sign of BRD. Any calf showing illness should be moved to the sick pen and treated before being run through the processing chute.

Processing Calves Safely Without Adding to Their Stress

A calm chute run on day one protects vaccine efficacy, reduces injury risk, and sets calves up to perform.

Vaccination and Parasite Control

Vaccinate healthy, rested calves on arrival against the four core respiratory viruses (IBR, BVD, PI3, and BRSV) as well as clostridial diseases. Research supported by USDA APHIS shows that over 80% of feedlots vaccinate for respiratory disease on arrival and for good reason. If calves are severely stressed or febrile, delay vaccination 24–48 hours until they stabilize; a suppressed immune system may not mount an adequate vaccine response.

Deworm calves if this wasn’t done pre-shipment. Internal parasites reduce both appetite and immune function, particularly in lighter calves coming off grass.

Implants and Procedures

Growth implants can be administered once calves have settled and are calm in the chute. Dehorning and castration, if needed, should be done after animals have had a chance to acclimate. Performing these procedures on newly stressed calves compounds recovery time and increases health risk.

Handling to Reduce Stress

After processing, walk calves to the bunk. This simple act does two things: it introduces them to the feed source, and it begins desensitizing them to human presence. Calves that learn early that humans mean feed are far easier to treat when issues arise later. For a deeper look at optimizing your feedlot operation from intake to closeout, Folio3 AgTech has a comprehensive guide worth bookmarking.

Feedlot Environment and Pen Setup

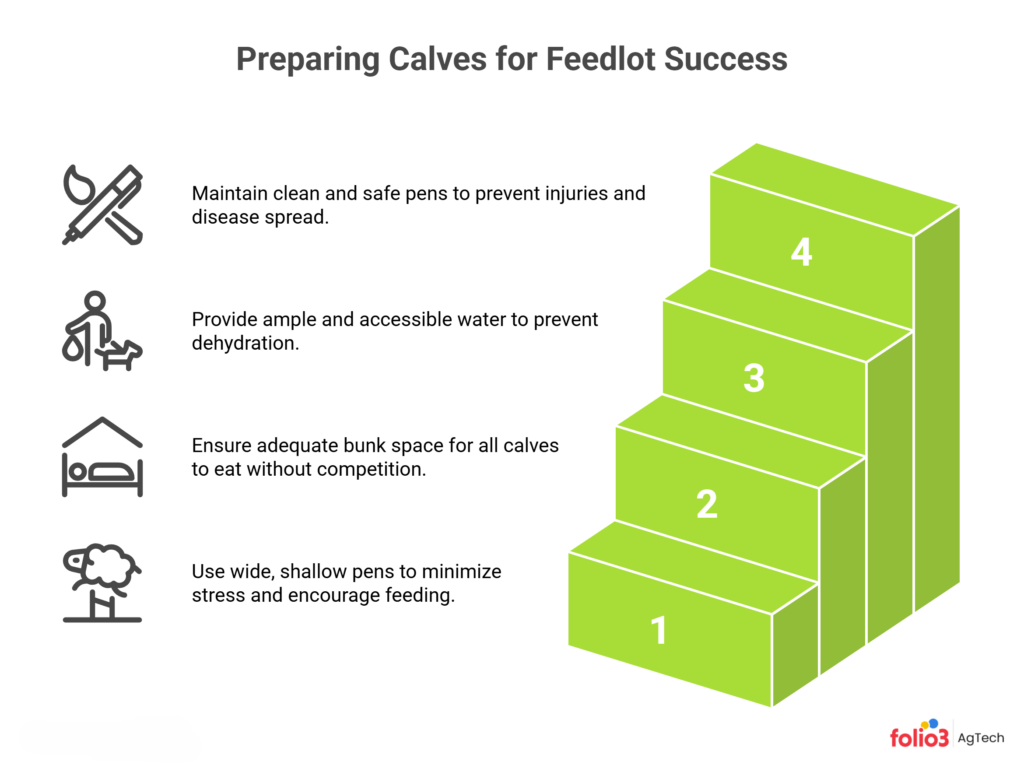

Even with perfect processing, calves placed in a poorly designed pen will struggle. Calf pen design directly affects how quickly new arrivals find feed and water, and that affects everything downstream.

Use wide, shallow pens for new arrivals. Large, deep pens encourage fence-walking and keep calves away from feed and water for extended periods. There should be a 60-foot pen depth with at least 12 inches of bunk space per head for the first 7–10 days. If your pens are larger, use temporary panels to subdivide them until calves settle.

Bunk and Feeder Space

Ensure every calf can eat without being pushed off the bunk. Aim for 12–18 inches of linear bunk space per head so timid or subordinate animals get access to feed. Remove any wet, spoiled, or moldy feed immediately. Fresh, palatable feed in front of an already stressed calf is non-negotiable. If self-feeders are in use, check the flow daily and remove them during the receiving period, as they prevent you from accurately monitoring intake.

Water Access

Water is the most critical and most overlooked nutrient during receiving. Dehydrated calves don’t eat, and calves that don’t eat get sick. There should be at least 1 linear inch of water tank access per head in the pen during transition, or the equivalent of 10% of the pen able to drink simultaneously.

Keep in mind that calves from pasture-based operations may never have encountered an automatic waterer. Add small bubblers or tie down float valves to simulate running water; some producers have had success with solar-powered bird bath bubblers in tanks to attract calves. Offering water immediately on arrival, even before feed, improves first-day intake. Clean water tanks at a minimum once a week and check them daily.

Safety and Biosecurity

Clean and inspect pens before arrival day. Broken fence boards, sharp metal edges, and deep mud are injury risks for newly arrived, disoriented calves. Keep new arrivals completely isolated from existing cattle, separate pens, separate waterers, and separate bunks. This is your most effective tool for limiting the horizontal spread of respiratory pathogens between groups.

Feeding Strategies for New Arrivals

Getting nutrition right during the receiving phase is arguably the most technically demanding part of managing calves in feedlots. The rumen is not ready for a high-grain diet on day one, and overfeeding is just as dangerous as underfeeding.

Building a Starter Ration That Gets Stressed Calves Eating

The best receiving ration is one that calves will actually eat; palatability matters as much as nutrition on day one.

Palatable, Nutrient-Dense Ration

Your starter diet needs to do two things: entice calves to eat and meet their nutritional needs while the rumen adapts. It should be palatable, well-mixed, and contain a complete vitamin and mineral package. Avoid cheap, unpalatable ingredients; a stressed calf will simply walk away, and the resulting intake depression sets the stage for BRD.

Forage vs. Concentrate

Offer long-stemmed hay free-choice during the first week. Prairie grass, oat hay, wheat hay, or Sudan hay all work well. Hay stimulates rumination and saliva production, which buffers rumen pH and protect against acidosis during the transition to grain. For lighter, more stressed calves, a 60–75% concentrate mix combined with free-choice hay works well.

Heavier, less-stressed calves can often handle a starting diet around 50–60% concentrate. Never introduce high-moisture corn or urea-heavy supplements during the receiving period; both can disrupt rumen function in animals not yet adapted to grain.

Avoid Abrupt Changes

A calf that arrived yesterday was eating grass this morning. The rumen microbes that ferment grain, particularly starch-digesting bacteria, need time to establish themselves. Shocking the rumen with a high-grain diet on arrival is a reliable path to acidosis, ruminitis, and liver abscesses.

Feeding Schedule and Intake Targets

Consistent timing and controlled amounts in the first two weeks protect rumen health and prevent costly digestive setbacks.

Frequent Feedings

Feed at least twice daily at consistent times. Consistency matters because cattle develop strong behavioral routines around feeding time, and irregular feeding schedules cause erratic intake, which contributes to acidosis. Replace leftovers with fresh feed; stale feed in the bunk discourages intake, especially in the first few days.

Gradual Intake Increase

Start conservative and build up. Set the following intake targets as a practical benchmark:

| Day(s) on Feed | Target Dry Matter Intake (% of BW) |

| Days 1–2 | ~0.75–1.0% |

| Day 7 | ~2.0% |

| Day 14 | ~2.5% |

Begin at roughly 1% of body weight in dry matter on day one, then increase by approximately 1 lb per head per day until calves are leaving a small amount of feed unconsumed. Never push intake faster than the rumen can adapt.

Rumen Transition

Plan for a full 3–4 week transition to your standard feedlot ration, as normal feed intake patterns don’t resume until approximately 21 days post-arrival. A practical step-up program looks like this:

| Phase | Forage (% diet DM) | Concentrate (% diet DM) | Duration |

| Arrival | 100% | 0% | Days 1–2 |

| Step 1 | 50% | 50% | Days 3–9 |

| Step 2 | 40% | 60% | Days 10–16 |

| Step 3 | 30% | 70% | Days 17–23 |

| Full Feedlot Diet | 20% | 80% | Day 24+ |

Monitor Intake

Track feed disappearance daily. If a significant number of calves go off feed, the first suspects are ration palatability and herd health. Getting feed intake management right during the receiving phase is one of the most impactful things you can do for long-term performance. For a detailed breakdown of how to improve feed conversion ratio using data-driven strategies, our guide covers practical techniques used by high-performance feedlots.

Monitoring Calf Health and Controlling Disease Spread in the Feedlot

Even with the best arrival protocol, some calves will get sick. Your daily observation routine and feedlot vaccination schedule are your earliest warning systems.

Daily Observation

Check calves at least twice per day, ideally at feeding time when their behavior is most revealing. Healthy calves come to the bunk eagerly. Animals that linger at the back of the pen, stand apart from the group, or show no interest in feed, need immediate investigation. Take rectal temperatures on any suspect animal; anything above 103.5°F warrants action.

Sick Pen Protocol

Move ill or weak calves to the sick pen promptly. Early intervention dramatically improves treatment outcomes and reduces pathogen spread to pen mates. Work with your veterinarian before any animals arrive to establish treatment protocols. Ensure the sick pen has its own feed, water, and handling equipment to eliminate contamination pathways.

Vaccination Plan

Adhere to your pre-arranged calf disease prevention protocol. Even if calves were vaccinated at the farm, a booster for respiratory and clostridial disease on arrival is standard industry practice. If calves arrive severely stressed or actively ill, delay vaccination 24–48 hours until they stabilize, as vaccinating a sick animal wastes product and can mask symptoms.

Parasite Control and Biosecurity

Deworm calves coming off grass if there’s any uncertainty about prior treatment. Internal parasite burdens suppress immunity and reduce feed intake, compounding the stress of receiving. Apply external parasite control according to season and region.

Do not allow shared waterers or bunks between different source groups. Disinfect sorting chutes and processing equipment between loads. Managing top challenges in feedlot management, including disease spread, is far easier when biosecurity is built into standard operating procedures.

Low-Stress Handling Techniques to Reduce Calves’ Stress and Build Trust

Stress is cumulative. Every rough interaction, every loud noise, every electric prod adds to the physiological burden a calf is already carrying. Low-stress cattle handling isn’t a luxury; it’s a performance tool.

Calm Approach

Use slow, deliberate movements around new arrivals. Solid-sided alleys and chutes prevent calves from seeing distractions that cause balking. Work within the animal’s flight zone, step into it to encourage movement, step out of it to let the animal settle. Experienced handlers should run the processing chute, especially on receiving day.

Desensitization

Spend a few minutes walking quietly through the receiving pen each day, particularly after feeding. Calves that associate human presence with calm, positive interactions become far easier to observe, sort, and treat. This small time investment in week one pays consistent dividends throughout the feeding period.

Gentle Sorting and Staff Training

Avoid unnecessary resorting after arrival. Every time the pen hierarchy is disrupted, cattle spend roughly 20 days re-establishing dominance, a period marked by reduced intake and lower feed efficiency. Sort once by size and health status, and leave groups intact as long as possible.

All workers who enter the receiving pens influence calf behavior. Poorly handled calves hide illness more effectively and underperform throughout the feeding period. Regular training on low-stress cattle handling is one of the highest-ROI investments a feedlot manager can make.

The Digital Feedlot: How AgTech Elevates Calf Success

Manual receiving protocols are only as good as the person holding the clipboard. Even experienced handlers miss early signs of illness, misrecord treatment dates, or lose track of which pen received which vaccine lot. That’s where modern AI livestock management tools close the gap, turning your receiving protocol from a memory exercise into a data-driven system.

Real-Time Intake Tracking

Traditional bunk scoring requires experienced eyes, consistent timing, and a reliable paper trail. Modern feedlot management software replaces the dusty clipboard with automated feed delivery records, pen-level intake dashboards, and deviation alerts when consumption drops unexpectedly. When a pen goes off feed at day 4, you know before the afternoon check, not the following morning.

Predictive Health Analytics

The hardest part of managing calves in feedlots is catching sick animals before they’re obviously sick. Behavioral sensors, weight variance tracking, and AI-driven health scoring models can flag “lethargic” calves based on movement patterns and intake anomalies that the human eye misses in a pen of 200 animals. Early intervention, even hours earlier, measurably improves treatment outcomes and reduces pull rates. Folio3 AgTech’s livestock health monitoring software is built around exactly this kind of proactive health intelligence.

Inventory and Treatment Logs

Withdrawal periods are one of the most critical food safety compliance requirements in the feedlot. A missed or miscalculated withdrawal on a treated animal can result in violative residues, rejected carcasses, and serious regulatory consequences. Digital treatment logs with automated withdrawal calculators ensure every antibiotic and implant event is timestamped.

FAQs

What Should I Feed Newly Arrived Calves on Day One?

Offer free-choice long-stemmed hay and clean, fresh water immediately on arrival. Hold grain or concentrate feed until calves have rested and are showing interest in eating. Starting too aggressively with energy-dense rations before the rumen is ready increases the risk of acidosis.

How Do You Reduce Shipping Fever Risk When Receiving New Calves?

Source from low-stress origins with verified health records and minimize transit time. Allow 6–12 hours of rest before processing, and vaccinate healthy calves against core respiratory and clostridial diseases on arrival. Separating new arrivals from existing cattle is equally critical to limiting disease transmission.

When Is the Best Time to Process Calves After Arrival?

Most professionals recommend processing within 24 hours of arrival, but only after calves have had adequate rest, typically 6–12 hours for stressed animals. Calves that are febrile or visibly ill should be moved to the sick pen and treated before running through the processing chute to avoid compromising vaccine efficacy.

How Much Bunk Space Do New Arrival Calves Need?

Provide a minimum of 12 inches of linear bunk space per head during the first 7–10 days. It ensures that timid or subordinate animals get access to feed and prevents competition-driven intake variation, which is a leading cause of acidosis in receiving pens.

How Long Does the Feedlot Transition Period Last for New Calves?

The full nutritional and behavioral transition period typically spans 21–28 days. Feed intake patterns remain erratic for the first three weeks as the rumen adapts to a grain-based diet. Plan your step-up ration program over this full period, and resist the temptation to rush grain inclusion. Slow transitions reduce digestive upsets and set calves up for stronger performance in the finishing phase.

FAQs

What Are The Management Practices Immediately After Calving?

Newborn calves should be dried, given colostrum within the first few hours, and monitored for signs of distress or illness. Proper housing, warmth, and hygiene help ensure a healthy start.

How To Handle A Calf?

Use slow, calm movements, and avoid sudden noises to reduce stress. Always support the calf’s body when lifting and use low-stress handling techniques to guide movement.

What Can You Do To Calm Down Cattle In A Feedlot?

Minimize loud noises and sudden movements, use proper handling facilities with curved alleys, and allow adequate space per animal. Consistent human interaction and low-stress handling reduce anxiety.

How Long Are Calves Fed In A Feedlot?

Calves typically spend 120 to 240 days in a feedlot, depending on their starting weight and the desired finishing weight for market readiness.

How Old Is A Calf When It Is Transported To A Feedlot?

Most calves enter a feedlot between 6 to 10 months of age, typically after weaning at around 500–700 pounds.

What Is The Diet Of A Feedlot?

Feedlot diets contain high-energy rations, including corn, silage, hay, distillers’ grains, and protein supplements to promote rapid weight gain and muscle development.