Regenerative grazing is everywhere; on beef labels, in webinars, and across social media, but most explanations still feel vague. Is it just moving cattle more often? Is it a climate “silver bullet”? Or is it simply good grazing with a new name?

Here’s the practical answer: Regenerative grazing is a goal-driven, adaptive way of managing livestock, so pasture ecosystems recover and improve over time. By the end of this guide, you’ll be able to set a realistic starting plan, track a few simple on-farm indicators, and separate useful principles from hype.

What Is Regenerative Grazing?

Regenerative grazing is grazing managed around a clear outcome: healthier ecosystem function on your pasture. In practice, you plan and adjust stock impact so plants recover quickly, roots rebuild, soil life is supported, and the water cycle works better (more infiltration, less runoff). The key point: it’s a management system that changes with conditions; rainfall, growth rate, and herd needs, not a single “magic” practice. You manage timing, intensity, and recovery together.

What Regenerative Grazing Is Not

Regenerative grazing is not “just rotational grazing.” Rotational systems can be excellent, but simply moving animals on a schedule doesn’t guarantee regeneration. Regenerative (often called adaptive) grazing is responsive: you shorten or lengthen grazing periods, adjust rest, and change stocking pressure based on plant recovery, residual left behind, soil conditions, and your goals, then you adapt again as conditions change daily.

Why Producers Adopt It (The Outcomes They Actually Care About)

Producers adopt regenerative agriculture grazing because it can make forage resilient in dry spells, keep the ground covered, and improve how rainfall is absorbed instead of running off. Many aim to stabilize animal performance by keeping pasture quality consistent and reducing erosion risks. The payoff is a more predictable grazing season.

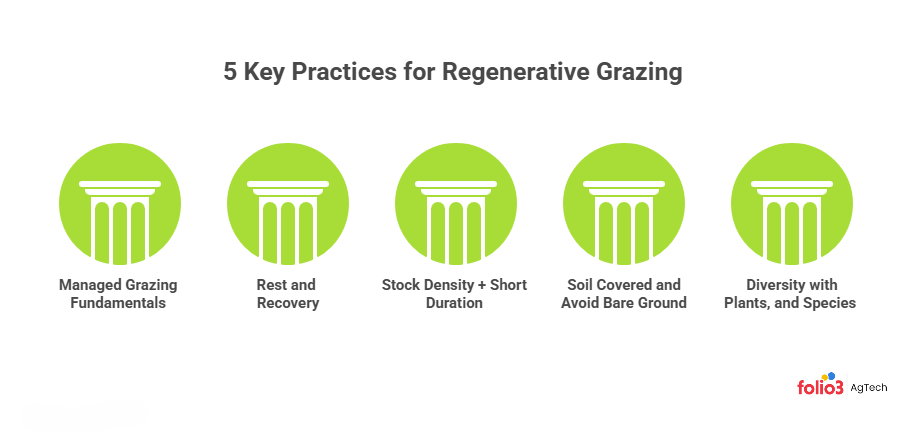

Regenerative Grazing Practices: The 5 Levers That Matter Most

Focus on the key techniques that make regenerative grazing successful, including stock density, recovery, and diversity.

The 3 Non-Negotiables (Managed Grazing Fundamentals)

If you remember nothing else about regenerative grazing practices, remember these three levers: grazing period, recovery period, and residual. The grazing period is the time animals stay on a paddock to keep it short enough that plants aren’t bitten again before they can respond. The recovery period is the rest plants need after grazing to fully regrow before you return. Residual is what you leave behind: enough leaf and ground cover to drive regrowth and protect soil. These fundamentals guide regenerative cattle grazing decisions, regardless of class, season, or forage type.

Rest & Recovery: Where “Regenerative” Is Usually Won or Lost

In most operations, “regenerative” is won or lost in recovery management. Instead of rotating by the calendar, you match rest to growth rate: fast regrowth in spring can mean shorter recovery, while summer heat or drought demands longer rest. Your job is to watch for signals: new leaves, a firm stand, and enough height to graze without scalping, then adjust moves accordingly. That observation mindset is the upgrade from rigid rules on your specific ground.

Stock Density + Short Duration: Uniform Impact Without Overgrazing

One of the most-used regenerative grazing techniques is pairing higher stock density with shorter grazing duration. When animals are concentrated briefly, they graze more uniformly, distribute manure and urine more evenly, and create a controlled “impact” that can stimulate regrowth. But it can backfire if you stay too long, push animals onto wet soils, or leave too little residual, then you get compaction, mud, and slow recovery. Density works only with rest and good monitoring.

Keep Soil Covered and Avoid Bare Ground

Bare ground is a cost you don’t see until you do: runoff, erosion, hotter soils, and slower regrowth. In regenerative grazing practices, you protect the surface with residual and litter, and you use brief, controlled grazing to trample some forage into ground cover. Just as important, you keep living roots in the soil as long as possible, roots feed soil microbes and improve moisture retention through drought and hard rains.

Diversity: Plants, and When Relevant, Multi-Species Grazing

Diversity is your resilience tool. Pastures with more species often handle stress better because different plants peak at other times, root at different depths, and respond differently to drought, pests, and grazing pressure. To encourage diversity, manage for recovery (so weaker species aren’t repeatedly grazed), avoid chronic overstocking, and consider adding legumes or warm-season forages where they fit. In some contexts, regenerative cattle grazing can also use multi-species grazing to spread impact and utilize different plants without chasing perfect mixtures.

Regenerative Grazing vs Rotational Grazing

If you’re hearing these terms used interchangeably, you’re not alone. The quickest way to cut through the noise is to separate the movement from the management. Rotational grazing is a tool: you move livestock between paddocks on a routine pattern. Regenerative (often called adaptive) grazing is a decision system: you adjust timing, stock impact, and recovery based on what the pasture is doing right now, so your grazing matches conditions and your outcomes stay in view, even as conditions change.

Rotational grazing means you routinely move animals to fresh forage. That alone can improve utilization, but it doesn’t guarantee regeneration. In regenerative grazing vs rotational grazing, the real difference is adaptation: you continuously adjust grazing period, stock impact, and rest based on pasture conditions. If growth slows, you extend recovery. If the soil is wet, you reduce impact. If the residual is getting tight, you move sooner. The goal is to synchronize impact with conditions and track what changes after each decision.

| Dimension | Rotational Grazing | Regenerative Grazing |

| Primary goal | Forage utilization | Ecosystem function + forage + profitability |

| Decision style | Prescriptive schedule | Responsive to recovery + conditions |

| Key metrics | Days in the paddock | Residual, recovery, ground cover, biodiversity |

| Risk when misapplied | Selective grazing, regrazing | Over- or under-impact; labor complexity |

| “Success” looks like | Controlled grazing | Better soil function + resilient production |

Which one should you implement first?

If you’re new, start with rotational grazing: get animals moving, get water and fences reliable, and learn what “good residual” looks like. Then make it regenerative by changing the driver from a fixed schedule to observation; adjust recovery length, grazing duration, and stock impact based on growth, moisture, and your goals.

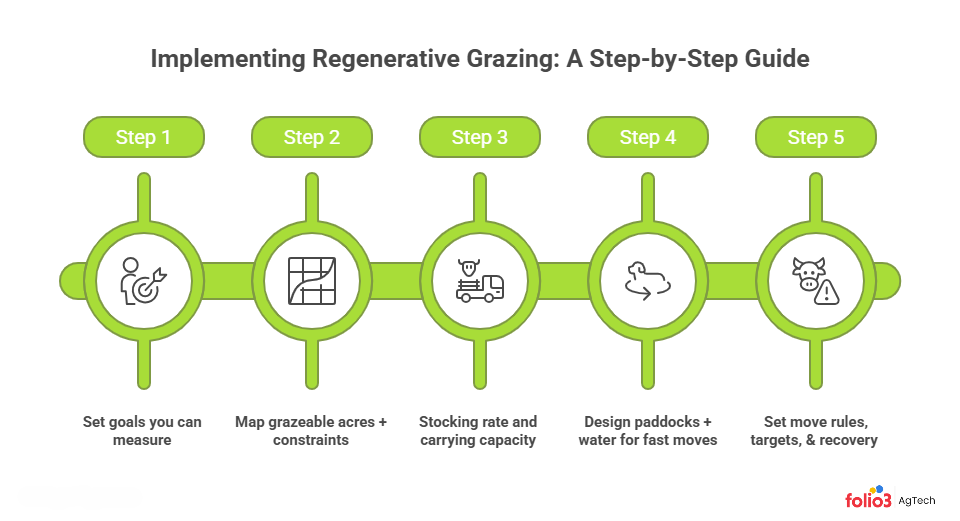

How to Start Regenerative Grazing (Step-by-Step Implementation)

A clear, actionable guide to implementing regenerative grazing, from setting goals to designing paddocks and recovery strategies.

Step 1: Set goals you can measure

Start by writing down 2–3 goals you can measure, because regenerative grazing practices are easier to manage when “success” is visible. Common examples include: extending grazing days, reducing hay fed, improving ground cover, improving water infiltration, or stabilizing average daily gain. Pick one leading indicator (like residual or bare ground) and one business indicator (like hay days). Then review them monthly before you buy new fencing. Keep the targets realistic.

Step 2: Map grazeable acres + constraints

Next, map your grazeable acres and constraints. Noble Research Institute recommends using aerial photos and soil maps to see the whole property, then marking infrastructure and forage types. Outline areas cattle can actually graze, and exclude heavy timber, brush, water, and other non-grazeable cover. On the same map, mark water access, shade, lanes, steep terrain, and “pinch points” that slow down moves. Be conservative; overestimating grazeable acres is a fast path to overgrazing. If unsure, start with your most reliable paddocks first.

Step 3: Stocking rate and carrying capacity

Then set a realistic stocking rate and carrying capacity. Noble calls stocking rate “the most important management decision,” because it drives everything else: plant recovery, soil cover, animal performance, and economics. In regenerative cattle grazing, most failures trace back to being a little too heavy for the growth you actually have. Use your grazeable-acre estimate, typical forage production, and planned grazing season to set a base number—then build in flexibility for precipitation swings and drought. Err on the conservative side.

Step 4: Design paddocks + water for fast moves

Now design paddocks and water so “fast moves” are realistic. Noble notes that adaptive grazing can change paddock shape and size, stock density, duration, intensity, and frequency, so you want layouts that stay flexible. Start with existing fences, then add temporary electric fencing (polywire and step-in posts) to subdivide as needed. If water is limiting, address it early; additional water sources may be required to optimize grazing management. Design for easy compliance: short walks, lanes, and setups you’ll actually maintain daily.

Step 5: Set move rules, residual targets, and recovery checks

Finally, set simple operating rules you can follow under pressure. Use the three managed-grazing principles, grazing period, recovery period, and residual to create your “move” checklist. For example: “Move when residual reaches X” and “Do not return until plants fully recover.” Add triggers for adaptation: extend rest during slow growth, back off impact on wet soils, and reduce stock pressure in drought. Write the rules down, review weekly, and adjust based on results. This is where regenerative grazing techniques become repeatable today.

Regenerative Cattle Grazing: Cattle-Specific Adjustments That Prevent Setbacks

Explore the cattle-specific considerations and adjustments needed for successful regenerative grazing, including nutrition and water management.

Match the System to Cattle Class + Season

Match your grazing plan to cattle class and season. Cow-calf pairs need steady intake and low stress; longer rest, and conservative residual usually beat aggressive moves. Stockers can handle tighter rotations to drive gain. Finishing animals may need higher energy and supplements. When growth slows (heat, drought, dormancy), reduce pressure and extend recovery to keep cattle comfortable and gaining.

Nutrition and Health

Good grazing can still fail if nutrition and health slip. Provide a mineral program matched to your forage base, and watch grass tetany risk on spring growth. Don’t turn hungry cattle onto high-legume paddocks; bloat risk increases. Monitor parasite pressure and body condition score (1–9); a falling score signals you to adjust recovery, forage quality, or supplementation.

Water, Heat Stress, and Welfare Logistics

If moves add labor but reduce welfare, the system breaks. In hot weather, cattle seek shade, drink more, and bunch around water; that’s a sign your layout needs attention. Plan paddocks so water access is reliable and practical for your terrain, and add shade options where possible. Design lanes and gates for calm flow, stress costs, gains, and reproduction.

Monitoring & KPIs: How You Prove It’s Working

Learn simple, cost-effective ways to track the success of your regenerative grazing efforts using field indicators and animal health data.

Field Indicators You Can Check Weekly

Weekly pasture checks keep regenerative grazing practices honest. Walk your last-grazed paddock and the one you’re about to graze. Look for consistent residual, regrowth speed, and bare-ground percentage. Note manure distribution, and whether cattle are leaving clumps untouched, uneven use can signal paddock size or water placement issues. Track species-mix trend: Are desirable grasses and legumes expanding or disappearing? Repeat after rain, frost, or heat waves to catch problems before they snowball.

Animal + Financial Scoreboard

Pair pasture notes with an animal-and-money scoreboard. Track average daily gain and body condition score on the 1–9 scale so you spot nutrition gaps early. Keep a count of hay-fed days and purchased feed per head; those are the economic levers. Log vet interventions and deaths, because health wrecks erase grazing gains. Finally, estimate pasture utilization by comparing planned grazing days to actual; your records should show whether pasture is replacing purchased inputs.

Recordkeeping Cadence

Keep recordkeeping light but consistent. Each week, not paddock grazed, days in, residual estimate, recovery days planned, and a quick note on weather. Once a month, review trends against your goals and adjust accordingly. Take repeat photos from the same marked points so changes in cover and species are obvious.

Regenerative Grazing Debunked: Myths, Limits, and What the Science Actually Supports

Bust common myths about regenerative grazing and explore what the latest science actually says about its climate benefits and limits.

Myth #1: “Regenerative grazing is always carbon-negative”

It’s a tempting claim: manage grazing well and your operation becomes automatically carbon-negative. In reality, regenerative grazing results are context-dependent—driven by starting soil condition, rainfall, plant growth, and consistent management over time. Soils also have a storage ceiling. Soil-carbon gains slowly as soils approach a new balance and can largely plateau after a couple of decades, so you can’t extend “early wins” forever. Carbon in soil can also be reversed by disturbance or severe drought. The practical takeaway: treat carbon-negative marketing as a claim that must be measured and qualified, not assumed.

Methane vs soil carbon + land footprint tradeoffs

Methane and CO₂ are not interchangeable in plain language. Cattle emit methane, and molecule-for-molecule, it has much stronger warming power than CO₂ over the near term, which is why methane can’t be waved away. At the same time, soil carbon can’t “offset forever” because sequestration slows as soils saturate and eventually plateaus in practice. You have to look at both sides of the greenhouse-gas balance sheet, not just the soil side. There’s also a land footprint tradeoff to acknowledge.

What does evidence suggest?

So what does science actually support? It strongly supports focusing on pasture function and resilience. For example, an open-access studyfound 30% higher springtime grass production and 3.6% higher topsoil carbon storage in that setting.That’s useful, but it’s not a blank check to claim universal carbon negativity. Do regenerative grazing for soils, water, biodiversity, and drought resilience, and communicate climate benefits carefully, with sources, to keep messages credible.

Where Regenerative Grazing Saves Money and Where Costs Move

Understand the financial impact of regenerative grazing, from cost savings in inputs to potential ROI through increased grazing days and productivity.

Cost shifts

Regenerative grazing practices shift costs rather than simply cutting them. You may target fewer purchased inputs by extending grazing days, but early investment is common. Noble notes that higher stock densities often require more temporary fencing, and some operations need additional water sources to optimize grazing management. Those infrastructure upgrades can raise upfront spend and labor, especially in year one. You’ll also spend management time planning moves and monitoring recovery.

Revenue upside pathways

Revenue upside usually comes from better pasture use: more grazing days, improved pasture productivity, and steadier animal performance through the season. Ground cover can improve drought tolerance, which protects the business in tough years. Some producers pursue premiums where verified markets exist, but don’t build your plan around that alone.

Simple ROI framing

Keep ROI simple. Track hay-reduction value (bales or feeding days avoided) and divide infrastructure spend by the additional grazing days you gained. If fencing and water added 30 grazing days, your “cost per added grazing day” gives a practical payback view you can compare year to year, for you directly.

Common Regenerative Grazing Mistakes

Even well-intended regenerative grazing practices fail for predictable reasons. Use this checklist to spot problems early and correct them fast:

- Overstocking beyond what current growth can support, forcing plants to recover while stressed.

- Coming back too soon, re-grazing before full plant recovery, which weakens roots and slows regrowth.

- Leaving too little residual, exposing soil, and cutting photosynthesis.

- Rigid schedules, moving cattle by the calendar instead of growth rate and conditions.

- Poor water or shade logistics are causing uneven grazing and stress.

- Ignoring wet-soil damage leads to compaction and long recovery times.

- Not tracking anything, so problems repeat unnoticed.

Note: These are management errors, not failures of regenerative grazing techniques themselves.

Troubleshooting Flow (If X, Do Y)

If regrowth slows, lengthen recovery and reduce stock pressure.

If bare ground increases, raise residual targets and shorten grazing duration.

If cattle bunch or avoid areas, improve water and shade placement.

Conclusion

Regenerative grazing isn’t a buzzword; it’s adaptive livestock management that builds soil health while supporting profitability. Your five levers are: keep soil covered (armor), minimize disturbance, maintain continual living roots, increase plant diversity, and integrate livestock intentionally. The key is monitoring, so use residual, recovery, and animal performance to adjust stocking rate and timing, not hope.

FAQs

What Are The Cons Of Regenerative Grazing?

The downsides of regenerative grazing usually show up during transition. You may face higher upfront costs for fencing, water, and planning, along with a steep learning curve. Results are not instant; some operations see short-term economic pressure before benefits materialize. Climate claims can also be overstated, as reaching carbon neutrality may require significantly more land than conventional systems. Scaling the model across large, commodity-style operations can be challenging without strong management capacity.

What Are The Best Cattle For Regenerative Grazing?

The best cattle for regenerative grazing are hardy, moderate-framed animals that thrive on forage and adapt well to changing conditions. Breeds known for grass efficiency and resilience, such as Hereford, Red Angus, South Poll, Galloway, Dexter, and Corriente, tend to perform well. Your environment, forage base, and management style matter more than breed labels alone.

Why Are Farmers Against Regenerative Farming?

Many farmers hesitate because the transition can feel risky. Upfront costs, possible yield dips during the first few years, and the need to learn new skills like soil biology, forage monitoring, and adaptive planning. Some are skeptical of top-down programs or fear increased labor demands early on. Without trusted guidance and peer examples, the change can seem overwhelming.

What Are The Benefits Of Regenerative Grazing?

Regenerative grazing can strengthen soil health, improve water infiltration, increase biodiversity, and support animal welfare by aligning grazing with natural systems. Over time, many producers reduce reliance on synthetic inputs, build more drought-resilient pastures, and stabilize performance. The long-term goal is a more resilient, profitable operation producing healthier animals and food.

How Many Cows Per Acre For Regenerative Farming?

There’s no fixed stocking rate in regenerative farming. A common baseline is one cow–calf pair per one to two acres over a year, but actual numbers depend on rainfall, forage growth, and management. With intensive, short-duration moves, large groups may graze a small area briefly, sometimes hundreds of cows per acre before moving on to allow full recovery.