Livestock fencing is not just about “keeping cattle in.” Done well, farm fencing is a management tool that protects animals, reduces injury risk, and makes grazing more efficient by guiding movement, protecting lanes, and supporting rotational plans.

In this guide, you’ll compare practical livestock fencing options the way an operator does, based on what you’re fencing, where you’re fencing, and how much time you can realistically spend on upkeep. You’ll also see why solid layout choices and good construction details matter as much as the material itself.

- The real goal: containment + safety + grazing efficiency (not just installation)

- The “best” fence changes with cattle class, predator pressure, terrain, and your management style, so your design should match your operation.

What Your Farm Fencing Must Do

Understand what you truly need your fence to accomplish to contain cattle, manage movement, deter threats, and support grazing efficiency before choosing materials or designs.

Contain Cattle, Exclude Predators, or Both?

Start by deciding what problem you’re solving: simple boundary containment, predator deterrence, or controlled movement through lanes and gates. A fence built only to “hold cows” can fail when calves, dogs, or coyotes change the risk profile, especially near calving, water points, or mineral sites.

Perimeter vs Cross-Fence vs Sacrifice and High-Traffic Areas

Think in zones, not a single line. Your perimeter fence protects the whole farm; cross-fences create paddocks for grazing control; and sacrifice or high-traffic areas need heavier materials. Planning the fence system upfront prevents costly “patchwork” fixes later and reduces daily labor.

Stock Class and Pressure Level

Fence pressure changes with animals. Cow-calf pairs may respect a simple barrier, while bulls and freshly weaned calves are more likely to test, lean, rub, or jump. Match strength and visibility to the highest-pressure group you’ll run in that pasture.

Terrain and Climate Realities

Your ground dictates what lasts. Wet soils can loosen posts, rocky ground can limit depth, and flood-prone areas can snag wire with debris. Snow load and drifting affect wire height and spacing. Choose post type, spacing, and braces for conditions.

Your Operating Constraint

Electric fencing can be an affordable option when you can power an energizer, build proper grounding, and keep vegetation off the hot wire. If you can’t keep it consistently “hot,” choose physical containment first, then add electricity where it helps.

Fundamentals That Decide the Performance of the Livestock Fence

Learn the core principles that determine fence strength, safety, and longevity, including tension, visibility, corners, grounding, and help you avoid the common cattle fencing mistakes.

Physical Barrier vs Psychological Barrier

A physical barrier blocks movement through the structure, such as woven wire or rail. A psychological barrier trains cattle to respect a boundary, which is why electric fences work well once animals learn them. Many farms combine both: a fence with a hot offset.

Corners, Braces, and Tension

Most farm fencing failures start at corners and ends, not midline. If braces are weak or tension isn’t managed, the wire loosens, the posts lean, and the gates stop latching. Invest in proper end assemblies, bracing, and strainers before you spend on wire.

Wire Spacing, Visibility, and Animal Behavior

Spacing and visibility shape how cattle interact with a fence. Too wide, and calves may push through or get caught; too tight, and costs rise. Add visibility (top rail, flagging, or tape) in training areas to reduce collisions and testing.

Electric Basics

An electric fence is only as good as its energizer, grounding, and maintenance. Poor grounding is a leading cause of fence problems, and vegetation contact can short the line and drain voltage. Keep the system tested and the line clean.

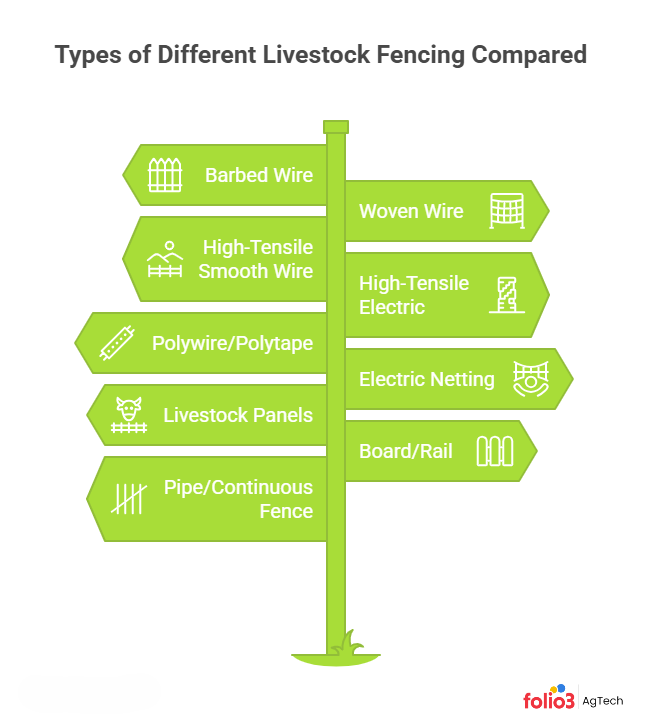

Types of Different Livestock Fencing Compared

Below is a practical comparison of the different types of livestock fencing you’ll see in real cattle operations. It is focused on what works, where it fails, and which livestock fencing options make sense for your goals in farm fencing and fencing livestock.

Livestock fencing options at a glance

| Fence type | Best for | Predator exclusion | Rotational grazing fit | Typical lifespan band |

| Barbed wire | Classic cattle perimeter on larger acreages | Low | Low | 33 yrs |

| Woven wire/field fence | Tight containment + better predator resistance | Med–High | Low | 33 yrs |

| High-tensile smooth | Long straight runs with fewer posts | Low | Low | 25 yrs |

| High-tensile electric | Cost-effective perimeter, offsets on existing fence | Med | Med | 25 yrs |

| Polywire/polytape | Cross-fencing for rotational grazing | Low | High | 1–3 yrs |

| Electric netting | Targeted containment/exclusion in small areas | Med | Med | 1–3 yrs |

| Livestock panels | Corrals, sorting, working alleys, short spans | Low | Low | 20+ yrs |

| Board/rail | High visibility and safety in select zones | Low | Low | 10–20 yrs |

| Pipe / continuous fence | Permanence + impact resistance | Low | Low | 20–40 yrs |

Barbed Wire (classic cattle perimeter)

Barbed wire remains a go-to for cattle fencing because it’s widely available and, in typical multi-strand builds, “very good at holding cattle.” It’s best on calmer herds and long perimeters, not tight pens or high-traffic lanes where animals push, rub, and accelerate injury risk. Reduce problems by keeping sag minimal, building strong H-braces/corners, and using good line-post spacing guidance for your design.

Woven Wire / Field Fence (containment + predator control)

Woven wire is your “close-the-gaps” option when you need stronger physical containment plus better predator resistance than barbed wire. Moreover, woven wire is excellent for predator control, and adding a high-tensile electric strand at the bottom can further deter digging or pressure at the base. It’s a strong perimeter choice for mixed-risk areas, but installation is more demanding, and material cost is typically higher than barbed.

High-Tensile Smooth Wire (non-electric)

Non-electric high-tensile smooth wire is built for long, straight runs, usually where you want fewer posts and a cleaner profile than barbed wire. When properly designed and constructed, high-tensile smooth wire fencing has multiple advantages, but it relies on disciplined tensioning and strong end assemblies. If your corners/bracing are weak, this is where you’ll see failures first—wires lose tension, then cattle learn they can test it.

High-Tensile Electric (perimeter or “offset hot wire”)

High-tensile electric is often one of the most cost-effective and adaptable livestock fencing options because it can serve as a primary fence or be added as an “offset” to protect existing barbed/woven/board fence from rubbing pressure. The cost of a permanent electric fence is much less than comparable barbed or woven wire fences, and it can help protect livestock from predators when designed well. The trade-off is management: you must keep the fence “hot,” and vegetation contact can short it out, so inspection and vegetation control are non-negotiable.

Temporary Electric: Polywire / Polytape (cross-fencing for grazing)

For rotational grazing, temporary electric (polywire/polytape/rope) is hard to beat for speed and flexibility. Moveable fences are commonly used to rotate pastures and adjust paddock size, but many temporary builds are not intended to replace permanent perimeter fences and may only last ~1–3 years in typical use. Use it for interior paddocks and lane control, not as your only perimeter for large cattle unless you’re set up to monitor and maintain it consistently.

Electric Netting (targeted containment/exclusion)

Electric netting is more situational for cattle. It can help with targeted exclusion or short-duration containment when animals are trained, but it’s less forgiving in tall grass and uneven terrain where shorts and tangles are common. Treat it as a “special-purpose tool” in your types of livestock fencing toolkit, not a universal perimeter. As with temporary fencing in general, expect shorter service life and higher hands-on maintenance.

Cattle Panels & Heavy-Duty Livestock Panels

Panels win where pressure is concentrated: corrals, sorting, working alleys, calving pens, and any short span where a cow can hit hard, and you cannot afford a failure. The strength is straightforward: rigid steel structure, fast setup, and high containment. The weakness is cost and misuse, as panels are expensive for long runs and fail when poorly anchored. Use them where you handle cattle, not where you merely “hold” them.

Board/Rail

Board/rail fencing is about visibility and controlled movement useful around homes, traffic areas, or select working zones where you want animals to clearly see the barrier. The trade-off is cost, and ongoing repairs and treated board fences carry a high relative cost and typically have a 10–20 year life span depending on materials and upkeep. For cattle, boards can still be pushed and broken in high-pressure zones, so plan accordingly.

Pipe / Continuous Fence

Pipe/continuous fences shine in feedlots and handling facilities where impact resistance and permanence matter more than per-foot economy. In these applications, you’re paying for strength, fewer “surprise failures,” and predictable control in pens and alleys. As a class, permanent fencing is commonly designed for a multi-decade life. The weak points are usually gates, corners, and corrosion-prone joints; design them like they’ll take hits.

Cattle Fencing Setups by Scenario

See proven cattle fencing layouts for cow-calf pastures, bulls, rotational grazing, and high-traffic areas, with clear guidance you can adapt to your farm.

Baseline Perimeter for Cow-Calf Pasture

For most cow-calf pastures, start with a durable physical perimeter and treat it as your “non-negotiable” boundary. Then add a single hot offset wire on insulators where cattle rub corners, shade lines, mineral sites to teach respect without rebuilding the whole fence, and simplify daily checks during busy weeks.

Bulls and High-Pressure Groups

Bulls, fresh weaned calves, and newly received stock will test your fence harder repeatedly. In these pastures, spend your money on structure: stout corner and end assemblies, deeper set posts, and hardware that won’t loosen. Avoid lightweight corners and “just good enough” bracing. So, once a bull learns a fence move, you’ll fight breakouts all season.

Rotational Grazing

If you’re rotational grazing, keep the perimeter permanent, then use temporary electric (polywire/polytape) inside to create paddocks and move cattle quickly. It is a practical system as permanent fences define the boundary, while temporary fences support rotational/seasonal grazing and can be moved as needed.

Laneways, Water Points, and Working Facilities

High-traffic areas deserve heavy-duty materials. Use lanes to move cattle between paddocks and a central working area, and place gates where movement is natural, often in corners and aligned across lanes. For pens, alleys, and water points where cattle crowd and push, panels or pipes reduce failures and gate damage.

Livestock Fencing Cost to Estimating Budget Without Guesswork

Break down real livestock fencing costs using credible benchmarks, so you can plan budgets accurately without relying on misleading per-foot estimates.

Cost Driving Elements

Livestock fencing cost comes from more than wire and posts. Corners and end braces add big material and labor hours, and gates can become a hidden budget line once you price heavy hinges, latches, and set posts. Terrain matters too: rocky ground slows installation, wet soils may require larger posts, and long straight runs lower your per-foot average. Labor is often the swing factor, so “$ per foot” can mislead.

Use Credible Benchmarks

To benchmark prices without guessing, use a comparison and then adjust for your local market. Building a straight quarter-mile (1,320-ft) perimeter fence across four permanent types: woven wire, barbed wire, high-tensile non-electric, and high-tensile electrified plus electrified polywire for interior use. Costs in the example were adjusted to 2024 prices, labor was valued at $20/hour, and the estimate includes equipment and tools. Notably, gates are excluded, so you can add them separately and avoid underbudgeting. It reports per-foot construction totals and annual ownership costs by fence type.

Cost-of-Ownership Thinking

Upfront cost is only half the picture. The annual ownership cost using useful life and maintenance assumptions: 20 years for woven and barbed wire, 25 years for high-tensile fences, and annual maintenance rates of 8% (woven/barbed) and 5% (high-tensile). That’s why a “cheap” install can become expensive if repairs and vegetation control pile up fast.

Planning + Installation Playbook for Cattle Fencing

Follow a step-by-step planning and build approach that helps you design, install, and inspect farm fencing correctly the first time.

Layout Planning

Before you set a single post, map your farm fencing on paper like a traffic plan. Sketch paddocks, laneways, and equipment access, then mark where cattle naturally flow to water, shade, and the working pens. Place gates for easy moves along lanes and measure each run so you can count corner posts, gate posts, and in-line braces accurately.

Build Order That Prevents Rework

A build order always keeps you from redoing work. Start with corners, ends, and braces first (they carry tension). Next, set line posts to the spacing your fence type requires. Then install wire or mesh and tension it gradually. Hang gates only after posts are solid. Finally, add electrification or hot offsets once the physical fence is straight and tight.

Quality Control Checks Before Turning Cattle In

Do a quality pass before cattle fencing goes live. Walk the line and look for wobbling posts, loose staples/clips, snag points, and low spots where calves could crawl. Check corners and brace wires for movement. If electric, test the voltage along the fence at multiple points and verify your grounding system.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Learn simple inspection routines and quick fixes that prevent common fence failures before cattle find the weak spots.

Inspection Rhythm

Do weekly quick “windshield” checks: drive or walk the perimeter, confirm gates latch, and spot insulators or posts starting to lean. Do seasonal deep checks before turnout and before winter: re-tension, reset loose posts, clear brush lines, and repair high-traffic damage after storms.

Common Failure Modes by Fence Type

Match your maintenance to the fence type. Barbed and smooth wire fail at corners, braces, and sagging spans. Woven wire fails at tears, lifted bottoms, and broken stays. Boards fail at fasteners. Temporary electricity fails from weak posts over time. Panels fail when poorly anchored.

Electric-Specific Troubleshooting

If electric performance drops, look for faults first: downed trees, heavy vegetation, or broken components. Using a voltmeter and keeping cattle fences around 3,000–5,000 volts, since soil moisture and vegetation load can change readings.

Safety, Welfare, and Legal/Boundary Considerations

Understand how proper fence design reduces injury risk, improves animal welfare, and helps you avoid boundary disputes and compliance issues.

Injury Risks and Visibility

In high-traffic cattle fencing zones, injuries often come from poor visibility and crowding. However, plank fences are easier for calves to see than wire, so set a plank at calf eye level. You can also flag thin wire at laneways and corners, and handle high-tensile tensioning with proper eye/hand protection.

Boundary Disputes and “Lawful Fence” Concepts

Fence placement doesn’t always match the legal boundary because a fence does not determine the boundary, and disputes may require a surveyor. Many states also define a “lawful fence” with minimum construction standards and cost-sharing rules, which can vary by state and county. Therefore, check your local requirements before building.

Modern Livestock Fencing Ideas

You can try practical technology-driven fencing ideas, including monitoring tools and virtual fencing for cattle cost with comparisons to improve control while reducing labor and downtime.

Remote Monitoring Add-Ons for Electric Performance

If you rely on electricity, remote monitoring reduces time spent hunting for shorts and low voltage. IoT monitors can clip onto the fence, send voltage readings to a dashboard over LoRaWAN, and trigger SMS/email alerts when voltage drops, so you respond before cattle test the line. A simple live fence indicator light can confirm that the voltage is above a set threshold.

Virtual Fencing

Virtual fencing uses GPS collars to create an “invisible” boundary. When cattle approach the virtual line, collars provide an audio cue and, if needed, a mild electric pulse. It’s promising when physical fences are hard to build or when you need frequent boundary changes. Physical fence is still essential on property lines, road edges, and other high-liability interfaces.

The “Right Fence” Is a System, Not a Product

The ‘right’ livestock fencing starts with your job-to-be-done: keep cattle where you need them, protect animals and people, and make grazing moves easier. From there, choose materials that match your stock class, terrain, and how consistently you can maintain the line. In practice, the best farm fencing is a system with durable perimeter containment, flexible cross-fencing for grazing control, and overbuilt high-pressure zones. Tracking which paddocks animals occupy and when they move helps you refine rotation schedules and evaluate whether your fencing layout supports your grazing strategy or creates bottlenecks. If you want a clear plan, we can run a fencing audit that reviews layout, total cost of ownership, and grazing-efficiency impacts, then map an optional smart-fencing roadmap.

FAQs

What Is The Best Livestock Fencing For Cattle Pastures?

The best cattle fencing really comes down to what you’re trying to achieve and how much time and budget you can commit. Many producers choose high-tensile fixed-knot woven wire when long-term strength, durability, and low maintenance are the priority. Electric fencing is often the most budget-friendly and flexible option, especially if you’re managing rotational grazing.

Is Electric Fencing Safe For Cattle, And What Makes It Effective?

Yes. Electric is a psychological barrier: cattle respect it when the voltage and grounding are right. It is recommended to use about 3,000–5,000 volts for cattle and regular testing.

How Can I Stop Cattle From Leaning Or Rubbing On Fences?

Can I Combine Different Types Of Livestock Fencing In One Farm System?

Yes. Pair a permanent perimeter with temporary electric cross-fences, then use panels/pipe in high-pressure zones. Cost benchmarks and build lists commonly separate perimeter from interior fencing.